This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

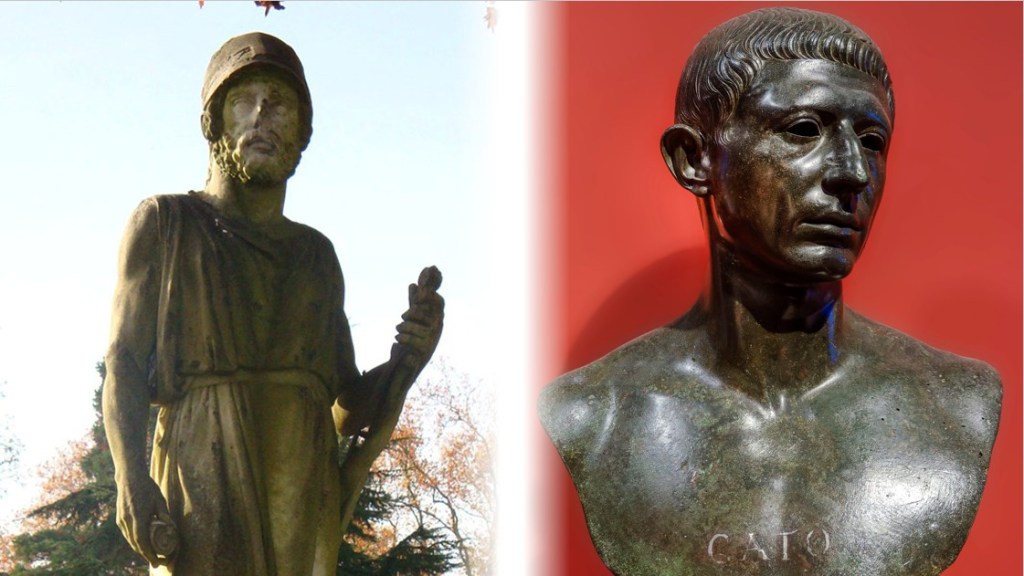

Phocion and Cato were two leaders who were renowned for their virtue and morals but whose hardline principles made them off-putting even their friends.

Phocion was an Athenian stateman and general during the time of Alexander and the Succession Wars that followed. He was considered one of the most honorable members of the Athenian assembly, but his commitment to honesty often made him a political outsider that most people also found insufferable.

Despite his annoying, “holier than thou,” personality, Phocion repeatedly served as strategos because the Athenian people admired his incorruptibility. He argued a prudent approach to Athen’s governance of its colonies, favoring diplomacy over brute force. He was a competent field commander and campaigned against the Macedonians in their conquest of Greece, besting Philip II, father to Alexander the Great, at least temporarily.

He cautioned Athens to endure Alexander’s reign and even to assist him at times and buy good will. When Alexander died, Phocion warned against launching a rebellion too quickly in case the news was false and encourage the retaliation of Alexander.

During the Succession Wars, Phocion tried to steer a prudent course for Athens, but one that was also often frustrating to his contemporaries that wanted to win glory or spoils of war.

Eventually, the Athenians turned on Phocion and sentenced him to death on an accusation of treachery, like Socrates. Like Socrates, the Athenians later came to regret their decision, realizing Phocion had been a competent and well-intentioned advisor of good moral character who cared primarily for the commonwealth.

Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (Cato the Younger) was born into a distinguished Roman family and was the great-grandson of Marcus Porcius Cato (Cato the Elder), the staunch opponent of Carthage. Like his ancestor, the younger Cato was well known for his frugality and morals, like Phocion, painfully so to the point of annoying even his allies.

He served briefly in Macedonia in a military tribuneship and then explored much of the eastern empire, trying to familiarize himself with foreign affairs and Rome’s further reaches in anticipation of taking an active part in politics upon his return to Rome.

Cato was a strong proponent of the Republic and quickly became an enemy of Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar, recognizing them as aspirational figures who would do anything for power.

When the Civil War broke out, Cato attempted to arrange for Pompey to have complete command of the armies opposing Caesar, but the Senate disagreed. Cato fled Rome and tried to hinder Sicilian grain supplies to Italy, to starve Caesar out. Cato was not present at the Battle of Pharsalus, and, following Pompey’s defeat, attempted to flee with him to Egypt before learning about Pompey’s murder by the Egyptians.

Cato then fled to Utica, in former Carthaginian territory, and tried to hold out against Caesar’s forces. Unable to do so, Cato killed himself. Caesar lamented Cato’s death, stating that he intended to pardon Cato, who himself had come to suggest that a hard line against Caesar had been ill advised and painted Caesar into a corner and forced his hand.

The diligence which Phocion and Cato stuck to their morals is admirable. However, it also was a disadvantage in their working with anyone of a different persuasion. Cato himself came to realize he may have in some ways caused the outbreak of the Civil War by leaving Caesar no off ramp from his actions. Similarly, Phocion’s stringent morality meant that he could not meet his constituents, the Athenian assembly, where they were on the issues of who to support in the Successor Wars. Phocion’s and Cato’s stubbornness hindered the ability of these otherwise admirable statesmen to effectively lead their governments and advise their polities.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment