This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

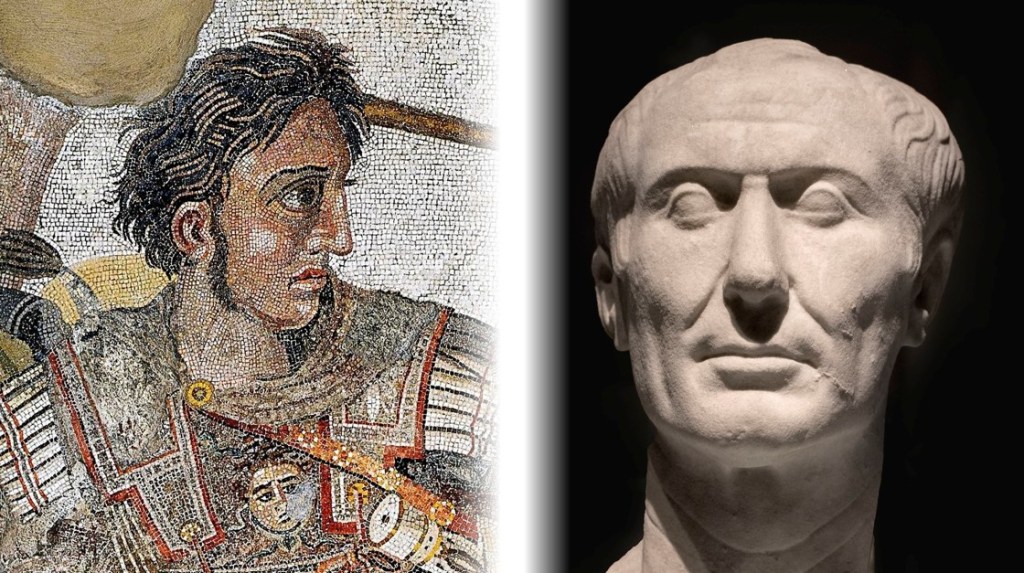

Plutarch handles the two giants of Ancient Greek and Roman history in an interesting fashion. On the one hand, they have the longest paired biographies in the entire text. On the other hand, he is far from glowing in his assessments of the two men. He certainly acknowledges their miliary prowess, but also sees their lives as cautionary tales about the dangers of boundless ambition and the waste that that can create. Both pushed and pushed, but to what end? Alexander’s empire collapsed as soon as he died, a victim of its own size and lack of structural supports. Caesar’s actions led to the end of the Roman Republic, a toxic system of imperial governance, and the slow decline of Roman power.

Both men took their respective military systems as far as possible, and their two lives together provide an interesting insight into the advancement of military operations and theory in the ancient world.

Alexander was the son of Philip of Macedon. He received a topnotch education and upbringing in preparation for taking the throne. He served alongside his father from an early age and was intimately involved in the Macedonian reduction and conquest of Greece. He ascended to the throne at the age of twenty, after the assassination of his father.

The Macedonian empire was far from secure when Alexander took the throne, and he worked quickly to consolidate power, striking against rebellious Balkan tribes and into Greece, which sought a chance for freedom. He ordered Thebes raised to the ground as an example for the rest of the Greeks. He also demonstrated magnanimity to rebellious Athens, showing that there could be carrots and not just sticks, if people cooperated. The Peloponnese voted to forgo rebellion and join with Alexander against the Persians.

He crossed into Asia with about 30,000 foot and 4,000 horse, or about 3.5 times what Xenophon, supposedly his inspiration for the expedition, had under his command when he fought the Persians. He engaged the Persians first at the river Granicus, where Alexander personally led a cavalry charge across the river. The battle was a complete success and most of Persian Anatolia fell into his hands, with only a handful of coastal cities holding out. He then debated whether he should press inland as fast as possible to engage Darius in person or secure the coast and his rear supply lines. He did the prudent thing and backtracked a bit until he could focus his complete attention on his main line of advance.

Darius had raised a massive army, reputedly ten times larger than Alexander’s. Though he was advised to stay in the plains of Syria, away from the sea coast, where he could use the size of his army to its full advantage, Darius passed through the mountains and engaged Alexander along the Mediterranean. Darius could not deploy his army in full, it being sandwiched between the mountains and the sea, near the town of Issus. Alexander again led from the front and routed Darius’ army, even capturing Darius wife and mother in the process.

With Darius’ forces scattered. Alexander again focused on clearing his flanks and reduced Persian-allied cities all along the Levant. He then proceeded to Egypt where he secured his position even more before continuing east in pursuit of Darius and complete control of Persia. He engaged Darius for the final time at Gaugamela, where he for a third time routed the Persian forces through a judicious tactical arrangement and personal leadership at the decisive point on the battlefield. He pursued separately both Darius himself and the last vestiges of the Persian army. Darius was killed by kidnappers, and Alexander finished off the remainder of the Persian army. He was in complete control of Persia.

He then engaged in a series of border conflicts, fighting as far north as the modern borders of Uzbekistan, east of the Caspian Sea. He also drove as far east as Kabul, Afghanistan and the headwaters of the Indus River, nearly on the border with China. He then descended the Indus, crossing into India. Then, at the request of his soldiers, he went back to Babylon. He planned to take out another expedition, never satisfied with what he had already conquered, but died before he could do so.

Caesar’s family had been allies of Marius, thus Sulla wanted Caesar dead. Caesar fled Rome and bribed his way into the eastern Mediterranean, where he hunkered down until Sulla was no longer in power. Back in Rome, he fought to revive the old Marian faction, more aligned with the people than the senate. He eventually received the governorship of Spain, but was in desperate need of money and so became a political ally of Crassus, then the richest man in the city. The two of them then began to work in concert with Pompey against the senatorial faction.

He then launched into the Gallic Wars. It was relatively easy for him to conduct the initial overthrow of Gaul, the tribes being disorganized and disunited. However, Gaul was much tougher to subdue long term, and Caesar spent many years conducting a counterinsurgency against the Gauls. He also conducted brief forays into Britain and Germany, much to the fascination and awe of the Roman people. There was a serious invasion of Germans into Gaul, which Caesar borrowed legions from Pompey to subdue. His campaigns earned he, his soldiers, and Rome tremendous wealth, and his soldiers became fiercely loyal to him as a result of nearly a decade under his personal command.

Back in Rome, there were concerns about Caesars’ growing power. Caesar in turn worried what his enemies would do to him if he didn’t have the protection of the largest army in the empire. The death of Crassus brought the conflict into the open as he and Pompey squared off for who would be the most powerful person in Rome.

Caesar stole a march on everyone and crossed the Rubicon River into Italy proper with a relatively small but highly mobile force. This cause his enemies to flee as soon as they could, and Pompey led the Senate east into Macedonia, the wrong direction, since the legion’s loyal to Pompey were in Spain. Caesar ignored Pompey and the Senate and rushed to Spain to knock out Pompey’s legions before turning back east to deal with Pompey himself. He defeated Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus, showing great skill in managing a large army as a leader, not a frontline combatant. Years in command of a a unified army provided Caesar with far more battlefield flexibility than most ancient generals had access to. In Gaul, he led from the front more often than not, but by Pharsalus, he was showing a calm maturity as a commander.

He then pursued Pompey to Egypt, where he found out Pompey had been executed in an attempt to curry favor with Caesar. Caesar punished those responsible and then became entangled in Egyptian politics before returning to Rome. He was awarded numerous offices by the new Senate and ruled as a singular head of state with a rubber stamp legislature. He was eventually assassinated by a cabal of senators who did not believe he would ever relinquish office like he said he would.

Explored together, the lives and Alexander and Caesar show how warfare had changed over the years in the Greek world. Alexander took the Greek system of hoplite tactics as far as it was possible to go. Those armies, composed of dense formations of spear-wielding infantry supported by cavalry on their flanks, could be arranged in interesting and useful ways pre battle by an enterprising commander. However, once battle was joined, there was little a commander could do to affect the outcome. Thus, good commanders took their time to get the army lined up, then joined their troops wherever they felt would be the decisive place on the battlefield.

The Roman system was different. They used smaller, more mobile, formations of sword-armed infantry. Roman generals learned over the years to use their armies in more flexible and dynamic ways than their earlier Greek and Macedonian counterparts had been able to. Generals like Caesar stayed back from the main action most of the time, managing battles and flowing in reinforcements as needed. They could personally lead assaults, but those were usually desperate moments when there was no more need or point to the general being removed from the front lines.

In many ways, Caesar was the high point of this system, as the Roman empire would spend the next five centuries involved mostly in domestic squabbles, limited punitive expeditions, and slow decline. In some ways, Europe would not see managerial generals like Caesar again for another 1500 years.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment