This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

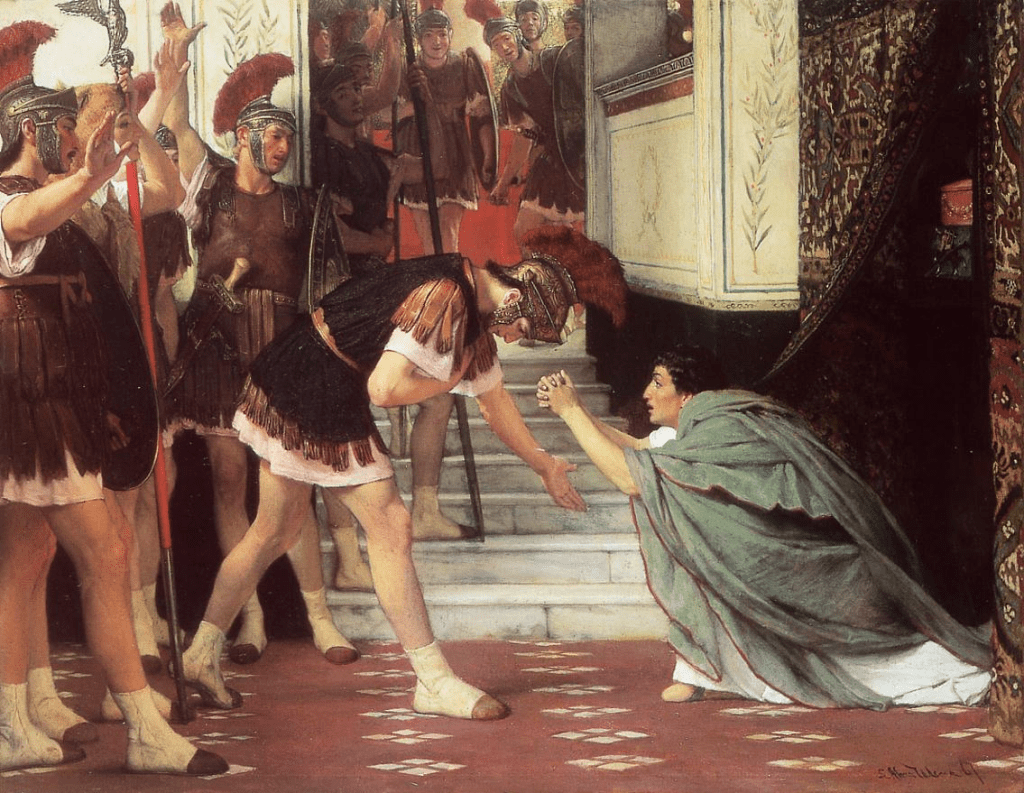

Claudius was in many ways an unexpected emperor. He had a number of physical infirmities because of an illness he suffered when young. During the court intrigues of Tiberius and Caligula, that probably helped him in the sense that no one really took him serious as a rival to the throne. However, after the Pretorian Guard assassinated Caligula, they declared Claudius emperor since he was one of the only living members left of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Claudius was very self conscious of his lack of military service and the fact that it had been the army who had made him emperor. Consequently, he paid particular attention to finding opportunities for the advancement and glorification of his military officers, while at the same time not running up too much against Augustus’ supposed advice not to expand the empire or the domestic concerns that Tiberius had contemplated: namely that highly successful generals were great candidates to be future emperors.

Claudius took advantage of smaller client states along Rome’s borders, annexing them when the opportunity arose from succession disputes or civil disturbances. Ostensibly these acquisitions were to preserve the peace and aid her allies, but leading these provinces became important sources for offices that Claudius could give out to his military officers.

One area where Claudius was hesitant to be king-maker was in Armenia and eastern Anatolia. The Roman east was the location of an uneasy peace between Rome and Parthia, a Persian kingdom centered on modern Iran but which extended well into the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys. The mountainous territory of eastern Anatolia was strategically important to both Rome and Parthia, but the two traditionally jointly selected the leadership there so that it would remain a neutral player and help preserve the balance of power between the two larger states.

During yet another bloody succession dispute Rome and Parthia needed to choose new leadership for Armenia. Claudius, despite the counterarguments of his military leaders on the ground in Syria, chose to not put a Roman puppet on the throne, desperate to preserve the peace and the status quo. The Parthians did not agree and sent an army into Armenia. However, a harsh winter in the mountains forced the Persians back. Armenia descended into relative chaos but the balance of power was maintained, at least during Claudius’ reign.

One area where Claudius did not head Augustus’ advice against expanding the empire was in Britain. The island had a semimystical place in the Roman imagination. It lay beyond the “Ocean” and even the (at this point) divine Julius Caesar had not advanced too far into what, as far as the Romans’ knew, was an entire continent. Claudius ordered an expedition to cross the English Channel, even showing up himself with war elephants at one point, and captured southern England for the Roman empire and pushing towards the edges of modern Wales and Scotland.

One thing that helped Claudius in his military efforts was the increasingly expanding system of Roman auxilia, non-Roman subjects of the empire, drawn from places like Gaul, North Africa, and the Danube Valley. These soldiers brought with them the skills and fighting styles of their parent cultures to a heavy-infantry-dominant Roman army. The base of the Roman army still remained the legion, soldiered by Roman citizens, which by this point operated from elaborate fixed fortifications, but the auxilia provided a mobile reserve and a “corps asset” of skills that the legions could use when Roman generals needed to build out taskforces for specific operations. Under Claudius, the auxilia became so important to the peace and security of the empire that they began to offer them Roman citizenship at the end of their term of service. What Rome did not want was a large Roman-trained population of suspect loyalty within its borders, better to keep the auxilia happy during and after their time in the army.

An emperor because of a palace coup, Claudius was acutely aware of how perilous his “supreme” position was. Tacitus regularly highlights the irony of extreme one-man rule: the more power he consolidates under him, the more paranoid he has to be about who might want to take it from him. For Tacitus, this level of one-man rule was a severe weakness of the Roman system. Sure, if Dear Leader is noble, educated, and competent, one-man rule might be great, but those individuals are rare and what happens in practice is a leader constantly distracted with palace intrigue.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment