This is part of a larger series I am working on.

Xenophon’s Anabasis, often translated as The March Up Country, is a fascinating look at Greek warfare at the tactical level. Unlike the sweeping political, strategic, or operational accounts of the Peloponnesian War that we find in Thucydides’ work, in the Anabasis we can smell the musk of the Greek hoplite, hear the ring of steel on steel, and feel the cold of the Armenian highlands in winter.

The Anabasis is also interesting because of how abnormal the situation of its participants was. Trapped more than a thousands miles from home, the Greek soldiers and their leaders, including Xenophon himself, had to push the Greek way of war to its limits and even invent new doctrine, on the move, in the middle of hostile country. The book shows the importance of taking the initiative, the benefits of tactical flexibility, and the power of encouraging innovative problem solving.

In 405 BC, the same year that Athens fell to Lysander and the Peloponnesian War ended, Darius II, the king of Persia, died. His sons Artaxerxes succeeded him, however, Artaxerxes’ brother, Cyrus, wanted the crown for himself and began assembling an army. With the largest war in Greek history over, thousands of Greek young men, briming with military experience, signed up with Cyrus as mercenaries, among them Xenophon.

Cyrus led them deep into Persian territory and fought his brother near the outskirts of modern Baghdad. While the Greeks were successful on their portion of the battlefield, Artaxerxes’ forces killed Cyrus and routed the rest of his army.

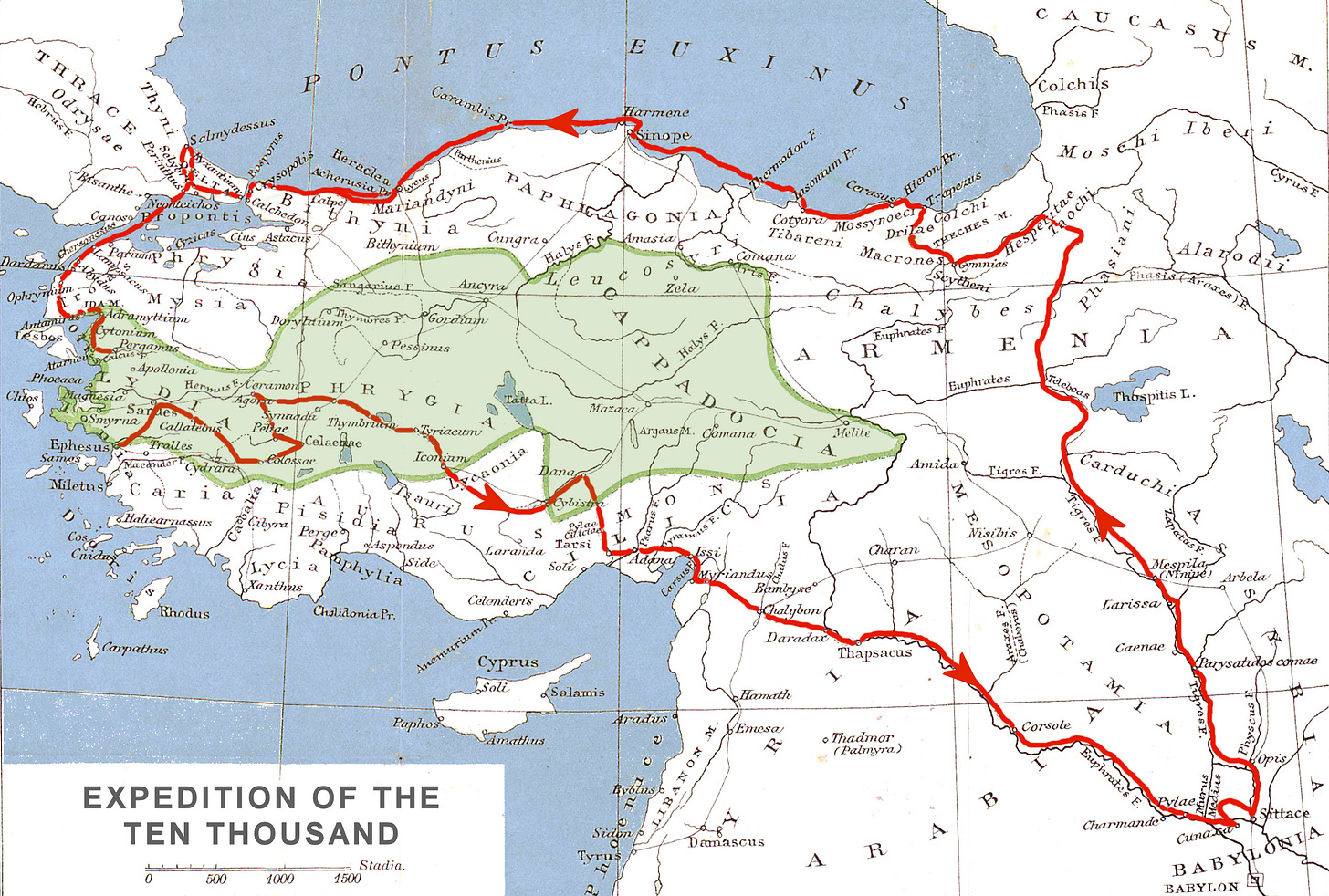

A standoff soon ensued, with Artaxerxes unable to destroy the Greek army that remained but the Greeks unable to travel back they way they had come. They eventually made their way north, fighting their way through modern northern Iraq and eastern Türkiye, to the Black Sea, shouting “Θάλαττα! θάλαττα!,” “Thalatta! Thalatta!,” “The sea! The sea!,” when it first came into sight. They then engaged various non-Greek tribes in multiple battles throughout the Black Sea coast, the Bosporus, and the Dardanelles on their way back to western Anatolia and Greece itself.

The soldiers of this force fought together from 401 to 399 BC, circumnavigating Anatolia. They became known to history as The Ten Thousand, and Xenophon’s account of their journey inspired a young Macedonian named Alexander to try his own march into Persian territory sixty-five years later.

One thing that immediately jumps out about Xenophon’s campaign is the sheer size of the force that had to survive deep within hostile territory. The famed “10,000” is a romantic oversimplification meant to make them seem even more beleaguered than they were. There were roughly 10,000 heavily armored hoplite heavy infantry. However, there were also an additional 4,000 supporting lightly armed and armored skirmishers.

With a total force of around 14,500 soldiers in the ranks, Xenophon and his fellow commanders were wielding a host larger than the entire army of Athens at the height of its imperial power. At the Battle of Mantinea, the largest land battle of the Peloponnesian War, and fought within roughly 35 miles of both Sparta and Argos, both cities committed only 4,000 soldiers to the engagement. When Athens launched its Sicilian expedition, the original force, the largest Athens had ever deployed for a single campaign in her entire history, they sent roughly 5,000 hoplites and around 1,000 supporting light infantry.

This was a very large army by normal Greek standards. Rarely in their history had the Greeks ever assembled a force this big, and few Greeks had any experience commanding, supplying, and organizing such a massive organization. In one sense, the size of the army was an advantage because it kept the Persians at bay, but on the other hand, its very size was a liability to its effectiveness in combat and was a logistical nightmare to try and maintain.

The other thing that made The Ten Thousand extraordinary was the distance they had to go and the length of time they spent together. Starting out from Sardis in 401 BC, they covered nearly 1,500 miles overland and by sea in the course of their roughly twenty-four-month long expedition.

Most Greek warfare was fairly localized. Armies did not tend to travel that far from their home city. Even in the case of Athens, who had regular experience with expeditionary warfare, the distances involved are slightly misleading. While Athens to the Bosporus or to the northern Aegean might take its soldiers 350 or so miles from home, they were never really that far from their supply caches aboard their ships because these were amphibious operations that did not go very far inland, and were only a few days at sea away from being back in Athens.

Greek campaigns also tended to be seasonal affairs because of their citizen-soldier armies. Typically, an army assembled in the spring, campaigned in the summer, and returned in time for the fall harvest because of agrarian manpower needs. The Spartans did have a “full-time” army because of their extensive use of enslaved helots, but the Spartans were also wary of having large amounts of their military away for too long at a time precisely because of its large enslaved population and the fear that it might rebel. These were armies that relied on simple tactics because they did not have the time to innovate, and, because their primary opponents had similar traditions and constraints, they did not really have the need to innovate.

With Xenophon and The Ten Thousand, we find a Greek army in a very different situation. They spent two years campaigning together and faced a wide array of tactical challenges. Consequently, they had to push Greek warfare to its very limits.

When Cyrus fought Artaxerxes outside of modern Baghdad, Xenophon and The Ten Thousand found themselves in the ideal tactical situation for a conventional hoplite army. They were directly across from their enemy, with the Euphrates River on their right and the rest of Cyrus’ forces on their left. The river provided a strong defensive barrier that kept any of Artaxerxes’ soldiers from attacking the unprotected righthand side of the Greeks, the side they carried their spears rather than their shields.

This scenario was perfect for The Ten Thousand. With the flanks of their phalanx secure, they could focus on attacking the enemy in front of them, and it worked almost to a fault. They routed the Persians in front of them, pursuing them so far that the Greeks did not realize that Artaxerxes’ forces had killed Cyrus, who had been overseeing the center of the army, leaving the continuation of the battle pointless.

Though the Battle of Cunaxa was a loss for the army The Ten Thousand were a part of, it represented the style of fighting they were used to, and they excelled in their portion of it. What Xenophon and his companions dealt with moving forward, was very different.

First, the hoplite heavy infantry of The Ten Thousand faced near constant harassment from opposing light infantry of various origins during their journey. The Greek skirmishers did what they could to alleviate this, but there was only so much they could do. This required the Greeks to maintain nearly constant march formations in a way that hoplite armies were not used to.

Traditionally, Greek forces would approach the battle site in loose marching orders appropriate to ease of movement on a road, capable of quickly crossing bridges, navigating defiles, and other impediments to march formations. They would then form a coherent fighting formation in preparation for the battle and disband after.

The Ten Thousand were in ranks most of the daylight hours of their march and the various impediments to marching plagued them as they tried to make their way north. The officers found that the men would bunch up too much crossing a bridge as they had to push their way across and then, on the other side, an accordion effect would take place as men rushed to reform their standard formation, creating dangerous gaps in the line that Persian cavalry could take advantage of.

So The Ten Thousand adopted permanent subunits that allowed them to compress and control the line of march in an orderly fashion. These roughly hundred-person formations seem not to have been intended for any tactical purpose but rather as an aid to command and control. Each could be easily overseen by one officer, who could help direct traffic in a coherent way as the army negotiated different obstacles.

The army as a whole became divided into four major commands: the front, the two flanks, and the rear (where Xenophon eventually commanded). These divisions were first developed, like the subunits mentioned above, for the purposes of cohesion and command and control on the march, but they eventually evolved into battlefield maneuver elements that could engage in relatively sophisticated tactics abnormal for hoplite armies.

One of the more interesting fights The Ten Thousand found themselves in was at the base of the Armenian highlands. They were still being pursued by the Persians at this point, but were far enough north that they were starting to encounter stronger independent tribal elements as well.

The Greeks needed to cross a river to escape the Persians but in front of them, contesting the ford, were Armenian tribesmen. They discovered there was a second ford down river and quickly developed a plan. Xenophon and the Greek rearguard would threaten a crossing at the primary ford, while the rest of the Greeks quickly forced their way across the secondary ford. This accomplished, the Greeks would be in a position to threaten the Armenian flank and drive them back.

Xenophon then turned his element around and engaged the Persians until the light infantry from the main army could recross the stream from the far said and provide their rearguard covering fire against the Persians while it crossed to the Armenian side of the river. Finally, the Greek light infantry crossed the river for a third time in the engagement, collapsing back to their support elements. The entire Greek army now on the Armenian side, the Persians needed to decide if they wanted to risk their own river crossing to pursue the Greeks. They chose to call it good on their pursuit of the Ten Thousand and report to Artaxerxes that they had successfully seen the Greeks out of his territory. Surely the Greeks would not survive the wilderness of the mountains on their own.

Nature itself was the enemy of The Ten Thousand in the mountains of eastern Türkiye. However, they did have one final fight before making their way into the Greek territory on the coast of the Black Sea.

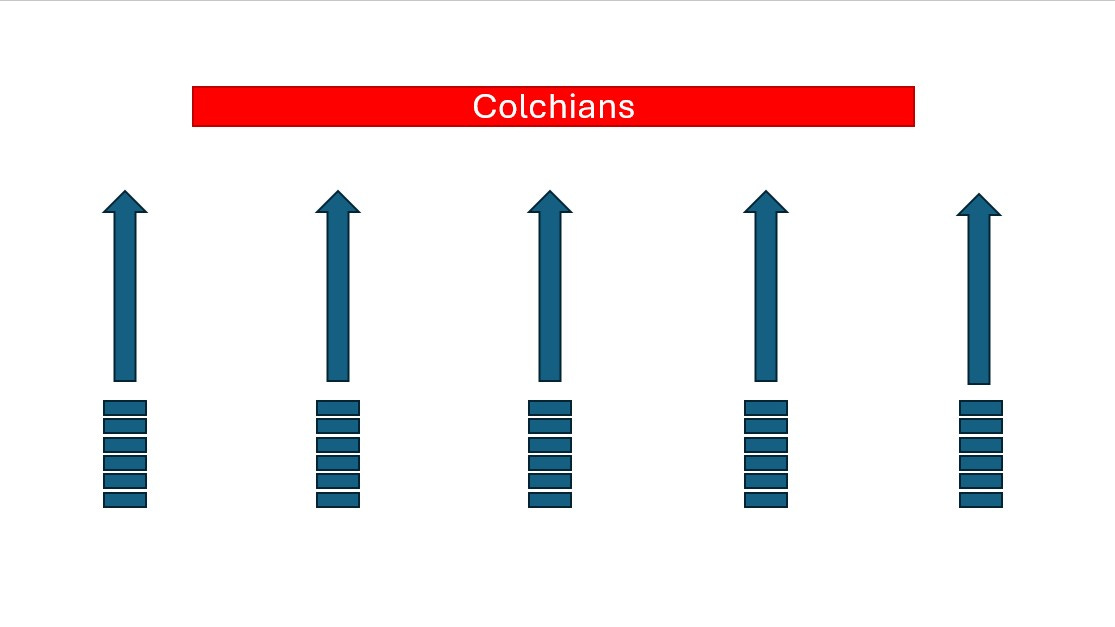

Opposing them at the top of a mountain pass was an army of Colchians. The Greeks at first intended to fight in their standard line a breast battleline formation. However, the route up was irregularly steep and filled with other bits of rough terrains that would have broken up the Greek advance, some parts of their formation ascending faster than others, opening gaps in the line and hindering their ability to make contact at speed.

So the Greeks decided to try an unconventional approach. They grouped a number of their roughly hundred-person subunits into attack columns, one behind the other. These larger formations then formed a line extended to the point where it would overlap the Colchians on either side, making sure they stayed spread out and their line as thin as possible. The Greek idea was to use these attack columns to breach the thinned out Colchian line at multiple points. The columns would be in a position to support each other if one got bogged down in heavy fighting, and then they would continue on their way past the Colchian position and to the Black Sea. This use of columnar attack seems to have been without precedent in the Greek world.

The Ten Thousand eventually made their way to the Black Sea coast and acquired shipping to the Bosporus and through the Dardanelles. They fought a number of other actions, even at one point using their light infantry in the gaps between attack columns in ways that feel very Napoleonic and was almost assuredly the inspiration for 18th Century military theorists like Guibert.

The Ten Thousand’s experience was unique. Never before and rarely again would a Pan-Hellenic army spend so much time together and have the opportunity to so mix together Spartan hoplite tactics, Cretan light infantry skill, and Athenian problem solving.

Xenophon’s Anabasis became required reading for many future military leaders, both in antiquity and in more modern times. The book provides a firsthand example of the power of combined arms tactics and the utility of maneuver in combat. It inspired Alexander to make his own anabasis into Persia sixty-five years later and provided a framework that European military theorists nearly two millennia later used to better conduct military operations in the rugged terrain of North America. It remains a critical piece of military theory.

Leave a comment