This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

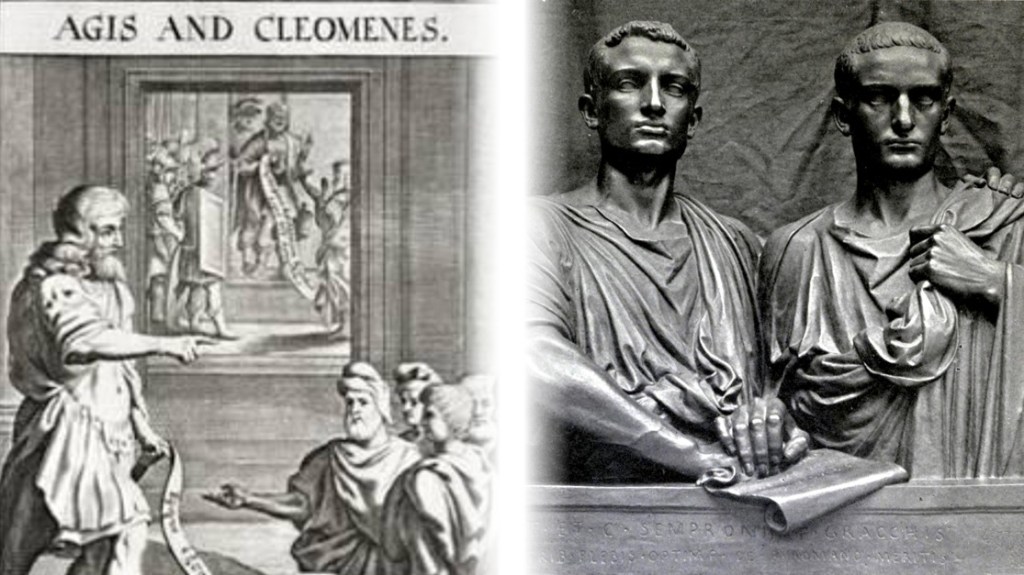

Agis, Cleomenes, and the Gracchi all tried to use the inspiration of an idealized past to make Sparta and Rome great again.

Agis was the product of a long line of impressive Spartans, born at a time when Sparta was far from influential. A city that had once been the ruler of the Greek world, Sparta was now a rump state wielding little power even in the Peloponnese. It’s conquest by Macedon and inability to play a major role in the Succession Wars that followed bothered Agis, their new king.

Agis felt that Sparta had gotten too fat and lazy. Too corrupted by gold and the foreign influences it had brought home during the Peloponnesian War and the imperial contests that followed its conquest of Athens. An increasingly small number of Spartans possessed more of and more of the land and wealth of the state. Agis wanted to reform Sparta and bring it back to the idyllic past established by Lycurgus.

To that end, Agis offered a series of reforms to the Spartan system: cancelation of mortgage debt, redistribution of land, restoration of the rigorous military education of Spartan youth, and the restoration of collective simple communal dinners. Not surprisingly, wealthier Spartans were highly opposed to these plans.

While Agis did manage to get the reforms passed, foreign affairs slowed their implementation and while Agis was away leading a war against the Aetolians, the wealthy Spartans deposed Agis and put a new king on the throne in his place. The ephors, the wealthiest of the Spartans, declared that Agis had tried to act as a tyrant by plundering them and executed him.

Cleomenes came to power as king of Sparta roughly fourteen years after Agis’ murder. His father had been an opponent of Agis and forced Cleomenes, at age eighteen, to marry Agis’ widow. She seems to have talked to Cleomenes a great deal about her first husband and his attempted reforms.

As a young king, Cleomenes had little time for domestic issues, however, and lead number of successful campaigns against the Achaean League. He worked with the ephors to expand his power, continue campaigning, and win many victories for Sparta. The whole time, though, he seems to have been preparing for what he would do upon his return to Sparta. Confident in the loyalty of his allies, Cleomenes ordered the death of the ephors, only one of whom escaped. He then implemented Agis’ reforms, to the celebration of the Spartan masses.

Sadly for Cleomenes, it wasn’t just the Spartan wealthy that were worried about what he was up to. Sparta had long favored oligarchies of democracies, and it had worked hard to make sure that more controlling and centralized forms of government were prevalent across the Peloponnese. The oligarchies on the Peloponnese invited in the Macedonian army and the rule by a king, rather than risk Cleomenes’ ideas and reforms spreading to their own cities. They ran Celomenes out of Sparta, and he then fled to Egypt, where he killed himself.

Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus were two brothers that lived in the late Roman republic, just before civil war between Marius and Sulla.

Both brothers were well educated members of the Roman middle class. Tiberius became tribune first, and while in office promoted and executed a series of economic reforms designed to relieve the poverty of the Roman rural poor. His primary tool in this was a survey of Roman public land in Italy, the reassertion of Roman governmental control of the land, and the redistribution of that land to the needy. To listen to Tiberius, this land had been illegally appropriated by wealthy Roman elites for their own use.

Elite reaction did not occur right away, but rather when Tiberius attempted to use money gained from foreign wars to fund the project. The senate objected to this on the grounds that Tiberius was attempting to go around them as an institution and therefore acting as a demagogic tyrant. He did not help himself beat these allegations by illegally standing for a second election and seizing the Capitoline Hill with his supporters to prevent a fair vote. He was killed in the ensuing struggle.

Gaius built on his brother’s legacy, winning election to the tribunate a decade later. He established a broader coalition of support, bringing in the urban poor into his camp and also the aspirational upper-middle class, the equites, who ranked just below the senatorial class. He promoted the idea of Roman colonization of conquered territories like Carthage and Spain.

Building such a large coalition, loyal to him through handouts was a threat to the senate and established wealth, and, like his his brother, Gaius was killed in mob violence during political disputes that boiled over.

While the senate never had the political leverage to repeal many of the Gracchi’s reforms, the use of violence by all sides became increasingly normalized. The Social War broke out not long after because of the land reforms, Marius and Sulla contested each other for supremacy of Roman politics, and the final political conflicts and military campaigns of Caesar and Pompey marked the end of the republic.

Agis, Cleomenes, and the Gracchi all looked to the past. What they failed to realize, was that times had changed. Neither city’s original governing systems were prepared for the challenges of the modern world and problems they found themselves facing. Their cities didn’t need to be forced back, they needed reforms that would let them move forward.

By engaging in backwards reforms, they not only alienated the existing stakeholders, guaranteeing a reactionary backlash, they failed to provide innovative forward-thinking solutions to their problems, creating chaos and limiting ways out of the trouble. By the end of their reforms, Sparta was again occupied by the Macedonians and Rome was in the midst of the republic’s death spiral.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment