This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

Plutarch seems to pair Cimon with Lucullus because both men were successful military leaders and statesmen that attempted to keep their respective cities unified, but who both ultimately failed.

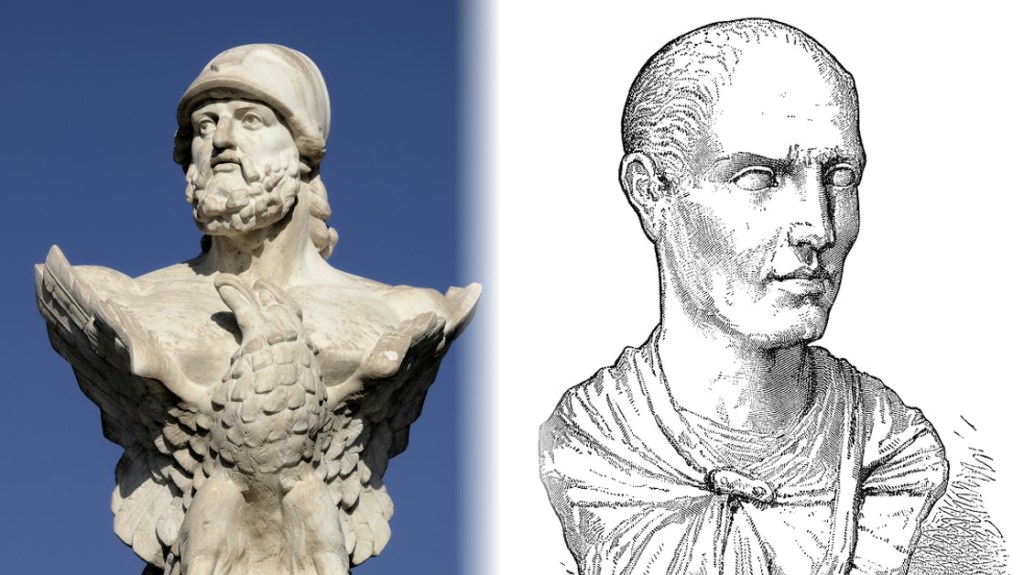

Cimon was an Athenian who came from a distinguished military family, his father serving at the Battle of Marathon against the Persians. Cimon himself later fought at the Battle of Salamis and was a competitor with Themistocles for Athenian operations and Pausanias for unified Greek operations against the Persians. He helped liberate Greek cities throughout Thrace and the northern Aegean that the Persians had captured previously.

Later, he oversaw the Delian League and as its member states at a time when more of them started to send money, rather than their citizens, as a contribution. Cimon oversaw the subsequent growth of the Athenian navy and used it to attack Persian positions throughout western Anatolia and secured a treaty with Persia that it would no longer operate naval forces in the Aegean or let its land forces come close to that sea’s eastern shore.

With the external threat to the Greek world taken care of, Cimon focused on Athenian internal politics. He was an advocate for the aristocratic faction in the city, believing it was a needed check on the democratic impulses of the masses. He worried that Athens’ newfound wealth would tempt the Athenians into adventurous military operations and risk an internal Greek conflict. He wanted to see the balance of power between Athens and Sparta preserved, fearing that a fratricidal conflict would open the way to foreign invasion.

Lucullus seems to have had similar concerns, even if the Roman situation was less dangerous than it was for the earlier Greeks.

He was a Roman commander that started his career under Sulla, during his early campaigns against Mithridates. Sulla tasked Lucullus with building a fleet in the eastern Mediterranean that could cut off Mithridates’ line of retreat as Sulla pushed east through Anatolia. The operation was a failure but did give Lucullus valuable experience as a naval commander.

He did not take part himself in Sulla’s civil war against Marius but did become one of Sulla’s favorites and a rival to Pompey. While Pompey was busy in Spain, Lucullus took command of anther expedition to the east against Mithridates. Leaning on his earlier experience, Lucullus launched a series of joint land and naval operations throughout Anatolia and the eastern Mediterranean, driving Mithridates back. Lucullus later drove inland through Syria and engaged both Mithridates and his Armenian allies. At this point, Lucullus’ expedition began to culminate, and Rome ordered Pompey east to help finish the job, inflaming the rivalry between the two men.

Like Cimon, Lucullus became involved in domestic politics upon his return from military operations in Asia. He grew concerned about the rise of Pompey, Crassus, and the popular faction that played to the masses. Similar actions by Marius had already led to one bloody civil war for Rome, and Lucullus worried about a second. Accordingly, he sided with Cato and Cicero in attempting to promote the Senate as an important institution. He seems to have been either too old or mentally unfit to take part in the later great disputes over Rome.

Both Cimon and Lucullus saw that their city-states had had dramatic success on the battlefield, and both also worried that those successes would lead to political excess and destabilization at home, threatening collapse. Both sought to find moderating influences that could preserve the gains they had fought for.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment