This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

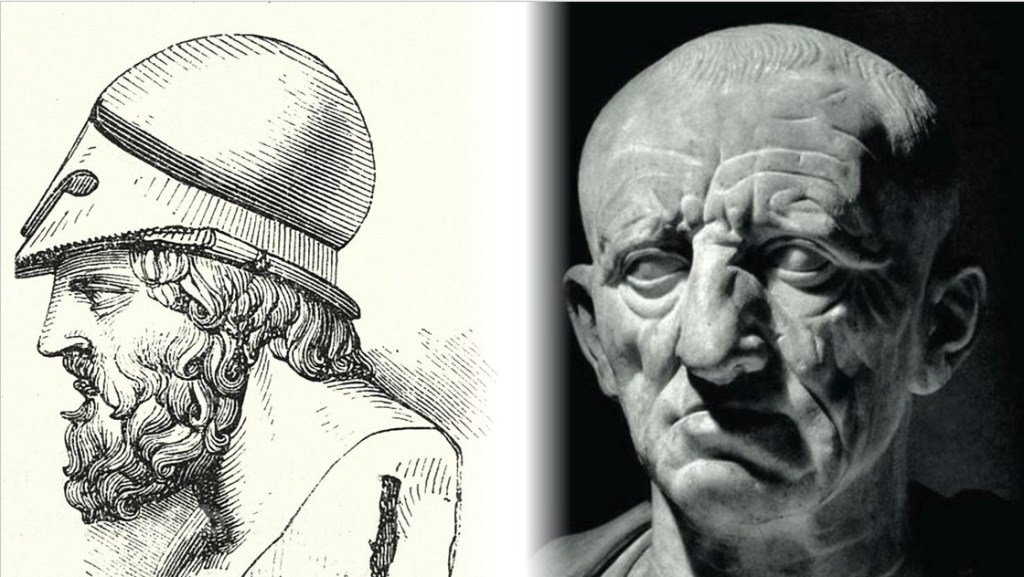

With his biographies of Aristides and Marcus Cato (Cato the Elder), we see a continuing focus by Plutarch on the importance of virtue in civic and military leaders.

Aristides was an Athenian at the time of the Greco-Persian War. He served at Marathon, and later at Salamis, where he advised Themistocles not to cut off the Persian retreat out of Greece, but rather to encourage their exit as soon as possible.

He later managed the Athenian-Spartan alliance and always focused on inter-Greek cooperation in the face of the larger Persian threat. This was especially challenging because the Greeks were a fractious conglomeration of ethno-linguistically related tribes, not a unified nation-state in any modern sense. He commanded the Greek forces at Plataea against the Persians and played a major part in Athens’ successful contribution to that land operation, an atypical feat because of its traditional focus on maritime operations.

After Plateau, Aristides was involved in the actions to roll back Persian forces in the Aegean. He won over many allies with his treatment of them as compared to the sterner and stricter demands of the Spartan Pausanias. He also had a reputation for aboveboard decisions, as opposed to Themistocles who wanted to damage the other Greek’s capacity for war and make Athens all powerful.

Lastly, he helped establish the Delian League and the taxes that supported it. When he originally assessed the taxes, they were fair. It was later Athenian demagogues, Plutarch informs us, who increased the taxes and created the angst the boiled over into the Peloponnesian War.

Cato the elder was a penny-pinching public servant of Rome who, along with Fabius, criticized Scipio for lavish spending. He later held command in Spain and conquered many cities alongside his Celtiberian allies. Scipio arranged for Cato to be replaced by him, and Cato was sent to Greece.

In Greece, he served with distinction and praised the Greeks for their ancient history. He led a force of Romans against Greek rebels dug in at the Thermopylae pass. Cato, knowing his history, found the famous trail around the pass and took the Greek force from both sides, ending the uprising.

He was elected censor and involved himself heavily in the affairs of Romans’ lives, trying to hold them to a very high standard of conduct. He was both famous and infamous for his frugality.

He later stirred up the Third Punic War, famously arguing “Carthago delenda est” (“Carthage must be destroyed”). He feared having such a powerful enemy only three days travel by sea from Rome, especially at a time when he felt Rome was becoming more and more intoxicated by the luxuries that the republic’s newfound empire brought into the city.

In both Aristides and Marcus Cato, we see leaders that believe personal, organizational, and civic virtue are all critically important. Aristides refused to take part in Themistocles’ plan to undermine the military capabilities of their fellow Greeks, even if it meant sacrificing Athenian dominance. Cato worried that his city was becoming too opulent and that the distractions of imperial bounty would hinder Rome’s ability to protect itself. For these leaders, it was not just important to win, it was important to win the right way, so that the success could be longer lasting and more durable.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment