This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

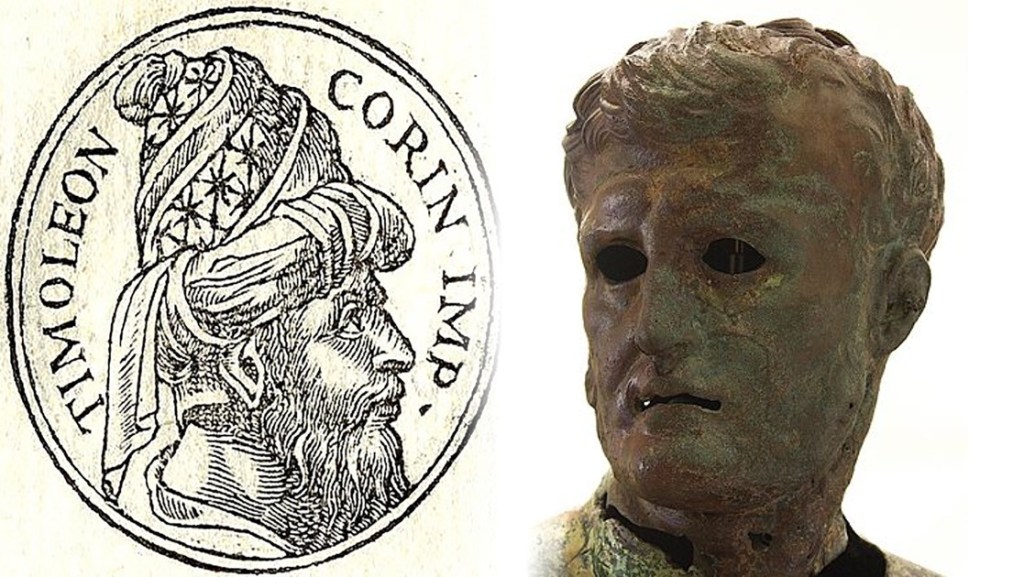

With his biographies of Timoleon and Aemilius Paulus, Plutarch continues a trend of focusing not just on the military prowess of his subjects but also their moral virtue. Indeed, his biography of Timoleon begins with a philosophical discussion of why he finds the investigation of virtue as, if not more, important than the martial character of his subjects.

Timoleon was a Corinthian born as the Peloponnesian War was winding down. At this point, Corinth was under a tyranny, led by Timoleon’s own brother. There was an uprising against the government and Timoleon committed fratricide rather than suffer the injustice to continue.

Given this professed hatred of tyrants, the people of Corinth selected Timoleon to lead a relief force to Sicily. Following the chaos of the Athenian invasion of the island, numerous despots gained control across Sicily, and Carthage, with colonies in western Sicily, backed these petty tyrants, playing them off against one another until Carthage could attempt to take the whole island. Syracuse, a former Corinthian colony, appealed to Corinth for aid.

Timoleon led a small relief force that used subterfuge and intrigue to gain a foothold in Syracuse and then gradually wore down the tyrants through a series of successful military operations. The Carthaginians sent relief forces of their own, but they were all beaten back by Timoleon and his soldiers. He used the security provided by his army to establish democratic governments in all the Greek cities on the island and, famously, died with little money in his possession, refusing to profit personally from what he saw as public service.

Many Romans held Aemilius Paulus in a similar light that the Greeks did Timoleon. Aemilius was the grandson of a distinguished former Paulus who had fought bravely at the Battle of Cannae against Hannibal. The younger Paulus was twice elected consul, the first time to deal with Gallic troubles in the Italian piedmont and a second time to counter Macedon and their king, Perseus.

According to Plutarch, Perseus was not highly thought of by his people and a tyrannical ruler. Amelius led the Roman army against the Macedonian phalanxes and used the greater flexibility and initiative of the Roman system to defeat the heavily armed Macedonians. Routing them, Aemilius proceeded to liberate Greece from the Macedonian subjugation it had faced since just before Alexander the Great.

Like Timoleon, Aemilius is said to have made no personal profit from this expedition. His only “prize” being a spectacular triumphal procession in Rome. This stands in contrast to many more famous Roman generals who undertook military operations specifically to expand their personal wealth, and therefore political power.

What Plutarch highlights is an expectation that public actors do not benefit privately from their public service. If they do, it is no longer a service to the public. This is especially true in matters of military affairs because of the unique power of life and death that military leaders hold. It is a shame that more people know the name Julius Caesar than Aemilius Paulus.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment