This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

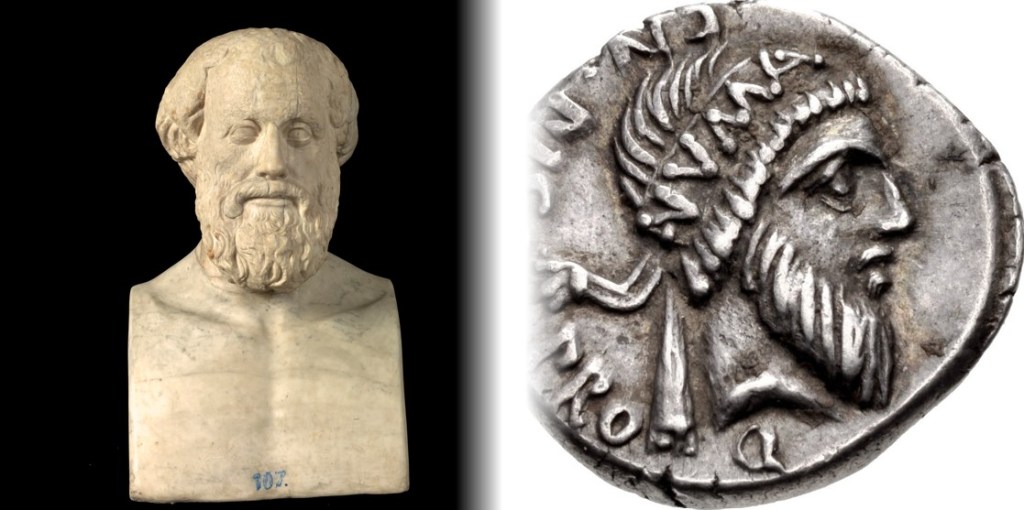

Lycurgus and Numa are an interesting pairing because both are famous for establishing the moral code of their respective societies, Sparta in the case of Lycurgus and Rome for Numa.

Lycurgus was born in Sparta but spent a good deal of time away. He traveled much of the eastern Mediterranean world, studying the legal systems in Crete, western Anatolia, and Egypt. He returned to Sparta after these travels and threw out the existing governing system with the aid of friends. That system was a tyrannical kingship and Lycurgus and others wanted to see a more balanced government in place.

Lycurgus established a dual kingship, along with a twenty-eight person senate. He also implemented land reforms that brought the wealth distribution as close to balanced as possible. His monetary reforms banned gold or silver, using large iron “coins” as money, the idea being it would be harder to bribe someone and such a hassle to spend that people would shy away from pursuing the acquisition of wealth as a primary motivator.

Lycurgus’ communistic system wasn’t just limited to fiscal policy, however. He also implemented simple communal eating for the men of Sparta, dining on their famous black soup; as well as a system of marriage designed to promote the growth of the city as the primary goal. If an older man could no longer have children and his younger wife could, the husband should let his wife have sex with the younger man if is would create new Spartans.

The Spartan education system was also communal in nature, designed to treat Spartan children as equal members of the community and promote unity. Their caretakers never provided them enough food so that they would be forced to steal and therefore learn stealth. It was a militarized society focused on winning the types of limited conflicts that occurred prior to the Peloponnesian War. Its focus was on training Spartans to stay cohesive in battle and win tactical encounters.

Numa had a different challenge in Rome. There the goal was not the deposition of a tyrant but how to knit a disparate community together.

Following the death of Romulus, Rome’s problem was it was an ad hoc amalgamation of people voluntarily or involuntarily joined to the city. The citizens of Rome elected Numa, a Sabine renowned for his honor and truthfulness, to be their new king. He at first declined, to his credit, but eventually acceded.

Like Lycurgus, Numa began on a long series of reforms for Rome. In his case, he tended to focus on religious matters, wrapping the city of Rome in divine sanction. It is Numa who established the Temple of Vesta and the order of the famed vestal virgins.

More importantly, perhaps, Numa, like Lycurgus before him, implemented land reforms, ensuring that the indigent all had access to some resources. It was not a communistic system like Lycurgus’, but was designed to mitigate poverty and class tensions. He also established trade guilds and societies so that people would tend to think of themselves first by their profession rather than by whatever city they had belonged to prior to living in Rome.

Numa was the only king of Rome never to fight a major war. His reign seems to have been very inward looking and focused on internal reforms. Rome’s neighbors were no doubt pleased by that, also taking advantage of the respite from conflict to avoid wars with Rome.

In all, Lycurgus and Numa offer individuals focused on the idea of how to create group unity. Both found some concept of equity to be important for avoiding tension and internal conflict. It is interesting, though, that Rome did not copy the Spartan model, which they were aware of. The Spartan system had serious drawbacks, and not just because of the limited food options. The Spartans were good at winning battles, but once wars became more than just one battle, the Spartan system struggled to adapt.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment