This is part of a larger project I am working on. These are just raw reactions to the text as I read it. For the final discussion, check out my Substack.

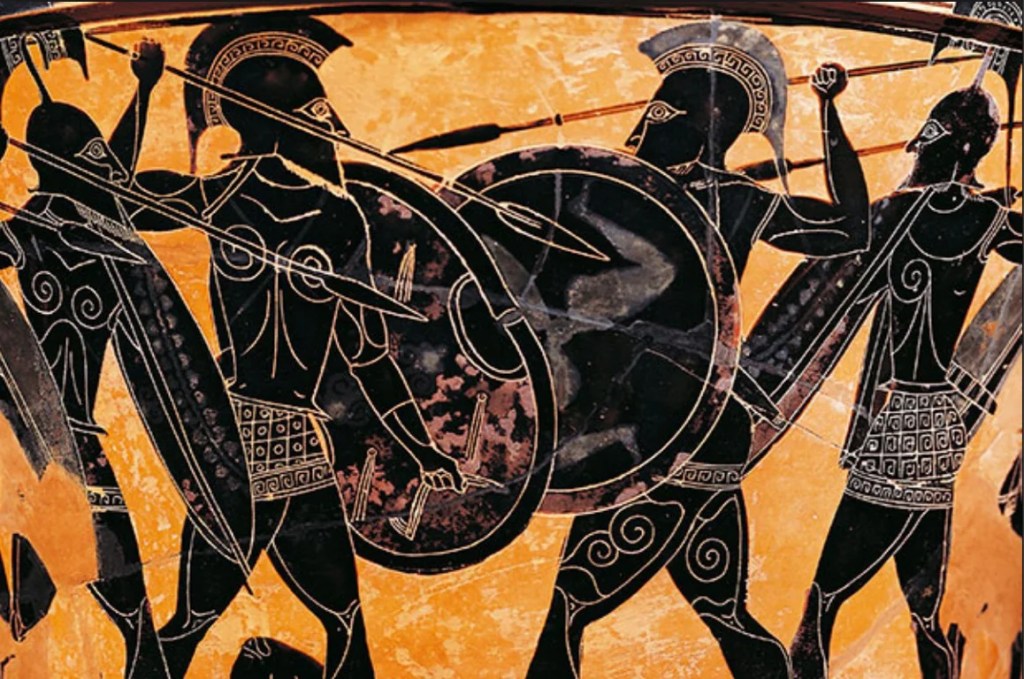

By 422, ten years into the conflict that the Peloponnesians had started, Athens was winning. With Athens capturing Pylos and Cythera, they were able to launch raids on Spartan territory and assist in insurrections of Sparta’s enslaved population. Sparta appealed for peace, but Athens at first refused. Luckily for Sparta, Athens soon suffered defeats at Delium, in Boeotia, and at Amphipolis, in Thrace. The two sides then signed the Peace of Nicias, named after the Athenian that negotiated it. Neither side really believed that peace would last, and both began talks with previously neutral cities across the Hellenic world.

The big prize would be Argos. This Peloponnesian democratic powerhouse was no friend of oligarchic Sparta, but Thebes and Corinth believed they could get the city to come into a future conflict on their side and help scare Athens into prolonging the peace. However, Athens was able to negotiate a treaty of its own with Argos, and she aided Argos in operations against Sparta but was careful not to do anything that would abrogate the larger peace treaty.

Argive-Athenian operations against Sparta culminated in the 418 Battle of Mantinea, which saw Argos and Athens defeated. The Spartans followed their victory by promoting an oligarchic takeover of Argos. For all the concern over which side Argos would choose, its involvement rapidly fizzled out to nothing and with Athens still on aggregate the greater power in Hellene and with Sparta and her allies still not really having a way to unseat her.

One problem Athens did have was keeping her subject cities in line. Brasidas had shown a model for aiding at least the continental cities, but Athens did not want to take any chances, especially with the islands in its empire.

The Athenians sent a fleet to the island of Melos, southeast of the Peloponnese. It had been neutral during the previous phase of the war, despite being a Doric colony with connections to Sparta. Athens declared that Melos must pick a side, and not picking Athens would result in immediate attack. Melos appealed to stay neutral. They were, they argued, an insignificant island of little use to either side. Athens countered, stating that precisely because Melos was so weak was why Athens could not allow Melos to be neutral. Athens could not let its subject islands see Melos enjoying freedom, lest it encourage the others to revolt and declare their own neutrality. “The strong do what they have the power to do,” said the Athenians, “and the weak accept what they have to accept.” This stands in stark contrast to Athens’ actions at Mytilene in 427, but Mytilene was already a subject of Athens, not a neutral. Thucydides also deftly documents the growing harshness of the conflict, and it could be that by 422 the Athenians were getting less tolerant of dissent or the risk of dissent.

If you’re interested in the final discussion of the book, check out my Substack.

Leave a comment